The table you fetch from a web API mysteriously contains an unexpected row with a null value in each column. You manually try the API using a tool like Postman or Insomnia and don’t find any all-null objects in the raw response. Where is this null table row coming from?

Zero rows (again!).

Previously, we dug into refreshes mysteriously dying with the complaint that “column ‘Column1’ of the table wasn’t found” even though no M code or data source schema changes had occurred. Upon investigation, we learned that an insufficiently in some fetch data M code results in it outputting zero columns when the web API returns no rows, which breaks later code that expects the presence of specific columns.

This time, zero rows is again the trigger condition, though it’s not zero rows altogether. Instead, it’s when a web API that returns paged responses returns a page containing no rows. Receiving back an empty page is a real-world possibility. For example, the last page of a response might contain zero rows because the rows that were to have been in it were deleted just moments ago, after the preceding page was fetched.

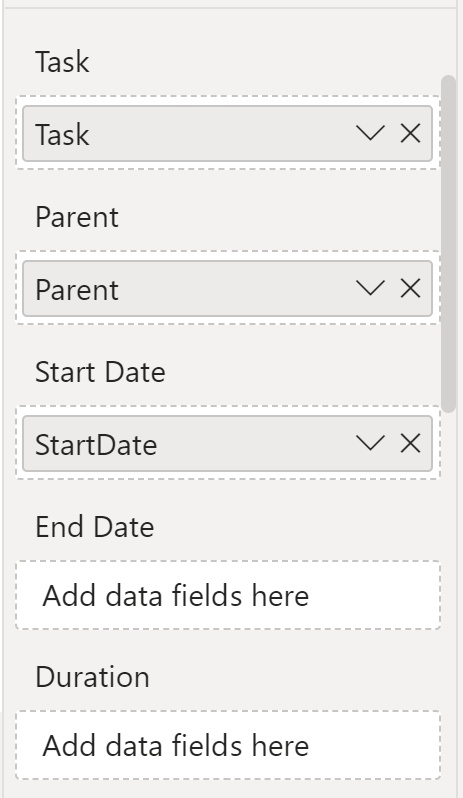

A common pattern for processing paged responses is to read the various pages into a list, then turn that list into a table, which is then expanded out into the appropriate rows and columns. However, the implementation of this flow sometimes leaves a corner case unaccounted for which leads to the all-null row being present. Unfortunately, such an oversight is present in Table.GenerateByPage (a function commonly used by custom connectors).

Continue reading →